I’ve been around RC aviation long enough that it stopped feeling like a “hobby” and started feeling like a weekly ritual. Sundays are flying days for the hobbyists, and there’s a calm (some not so calm windy days as well) predictability to it: field, transmitter, take off, fly, land, repeat, with nothing else competing for attention. It’s the one slot in the week where the world gets quieter and the only thing that matters is the aircraft.

Builds come and go, and I’m not trying to keep score. I am sharing the most recent, and it came out of a very practical need: developing a new wing for an aircraft that I crashed, pilot error ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. It’s a small peek into the kind of work I like doing and no testament of sorts.

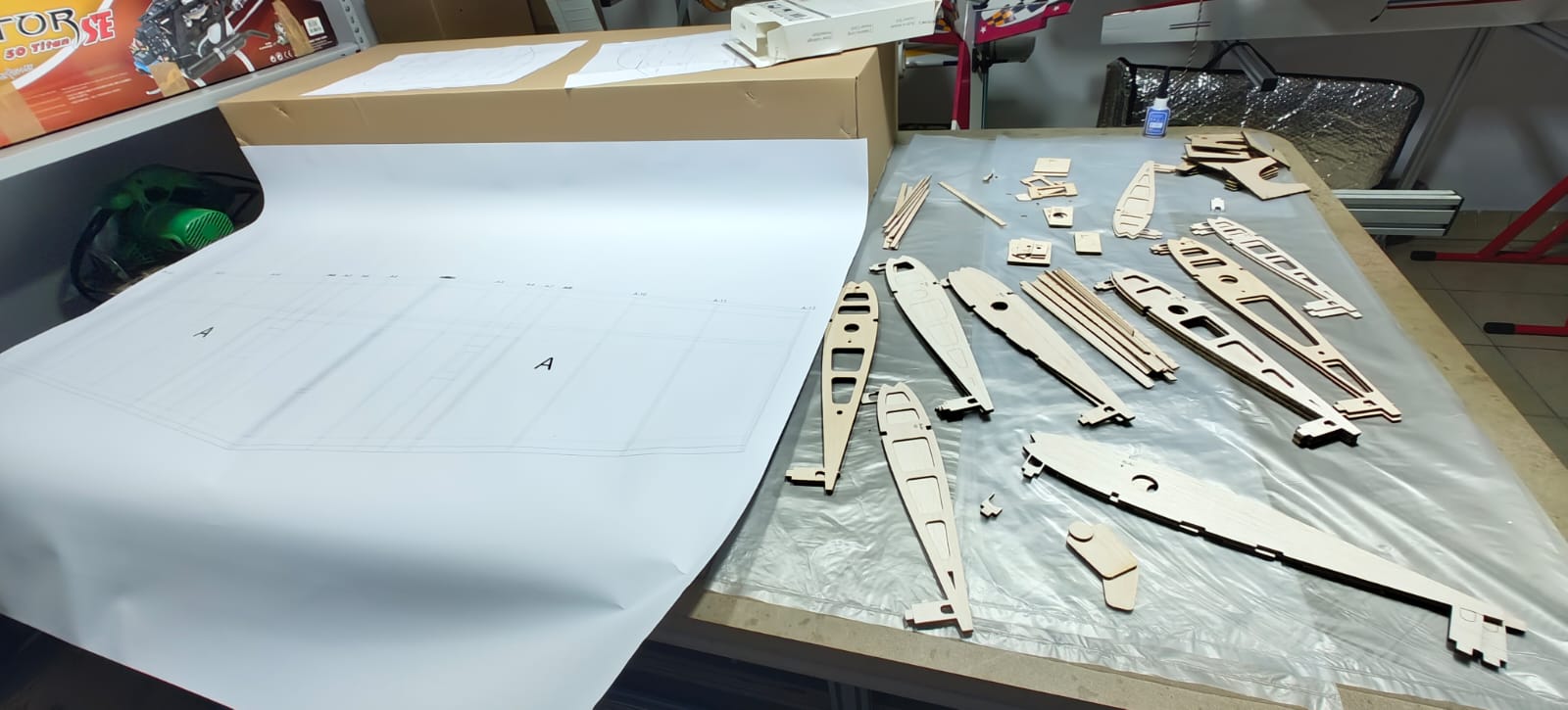

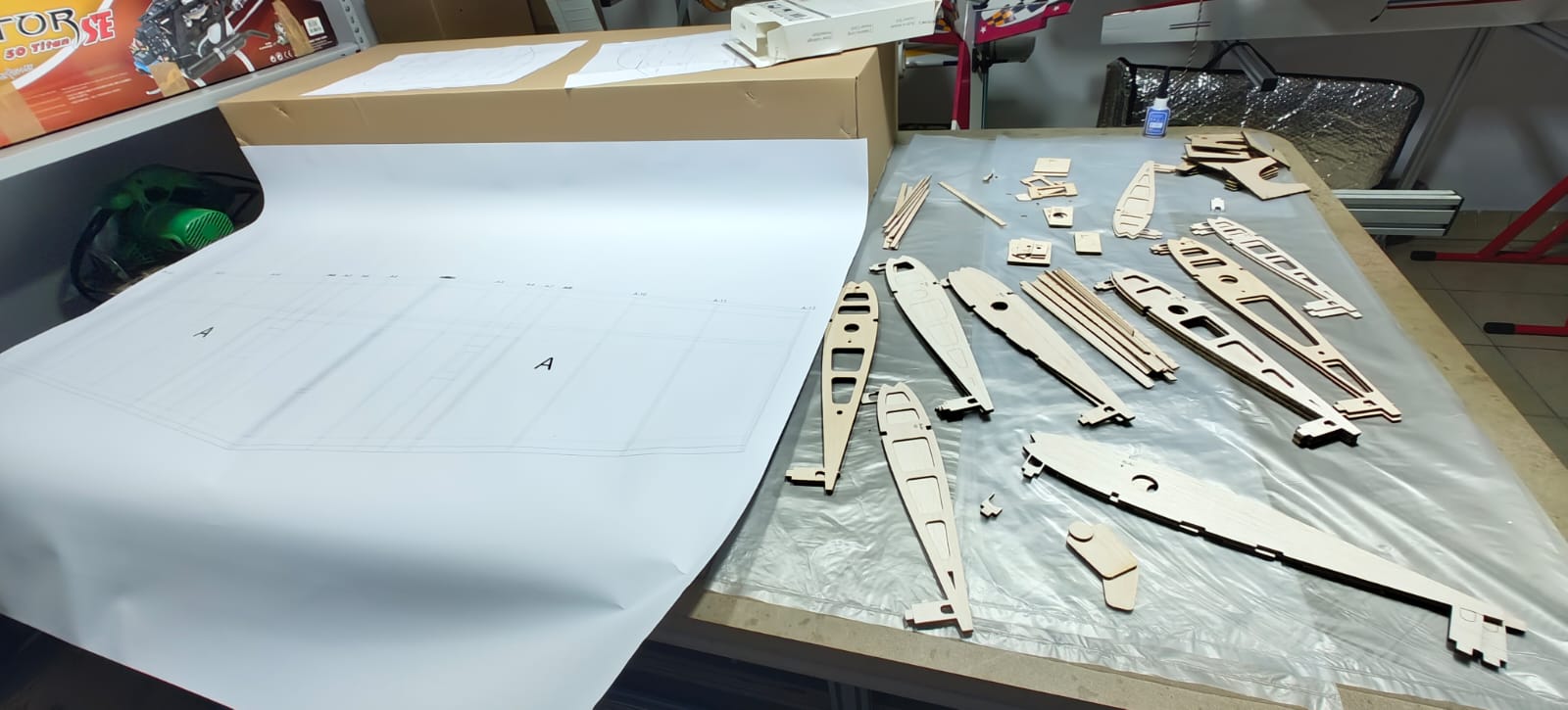

The process starts on a screen, in DevWing, where the wing geometry is defined and build plans are created.

Then it becomes wood. Laser-cut balsa looks straightforward until you realize every laser machine behaves differently, and the tolerances you assume are rarely the tolerances you get. So, there’s a small, annoying, necessary step where you calibrate for that specific cutter, adjust the leads and fits, and only then commit to a cut that actually assembles cleanly.

After that it’s the slow part: building to plan, keeping everything straight, and covering it properly, because tiny deviations compound and you only find out in the air.

What I get out of this isn’t just a “model airplane”. It’s a demanding, full-focus loop that forces patience and attention. When life is noisy, building and flying narrows my mind to one channel. By the end of the day, the stress is smaller, and my head feels reset.